Max2ae 4 0 Crack Cocaine

Crack: Power with My Girlfriend: Ben: Crack: Another Good Time: LSD Pirate: Crack Cocaine: Ritual Session with Crack: Msebunga: Crack: I Don't Like the Drugs, but the Drugs Like Me: Comfortably Numb: Cocaine & Crack: No Effects Whatsoever: Alexander Shulgin: Cocaine - Freebase: The Night That (Almost) Ruined My Life: Moke: Crack: A Balance of.

- Cocaine smokers suffer from acute respiratory problems including shortness of breath, coughing, and severe chest pains with lung trauma and bleeding. It appears that compulsive cocaine use may develop even more rapidly if the substance is smoked rather than snorted. High doses of cocaine or prolonged use can trigger paranoia.

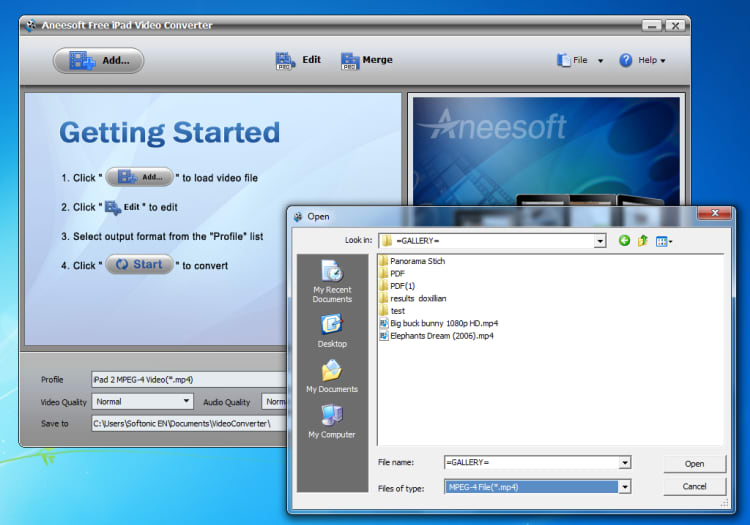

- Drpu bulk sms crack serial keygen minecraft cracked server tnt run otocheck 2 0 keygen mac comment installer un mod minecraft 1.7.10 cracked minecraft mount blade warband crack gezginler download como contra atacar no assassins creed 2 crack on my own karaoke full version max2ae 4 0 crack cocaine arliberator 3.

The crack epidemic in the United States was a surge of crack cocaine use in major cities across the United States between the early 1980s and the early 1990s.[1] This resulted in a number of social consequences, such as increasing crime and violence in American inner city neighborhoods, as well as a resulting backlash in the form of tough on crime policies.

In 1986, the U.S. Congress passed laws that created a 100 to 1 sentencing disparity for the possession or trafficking of crack when compared to penalties for trafficking of powder cocaine,[2][3][4][5] which had been widely criticized as discriminatory against minorities, mostly blacks, who were more likely to use crack than powder cocaine.[6]

- 5Post epidemic commentary

- 6Influence on popular culture

History[edit]

The name 'crack' first appeared in the New York Times on November 17, 1985. Within a year more than a thousand press stories had been released about the drug. In the early 1980s, the majority of cocaine being shipped to the United States was landing in Miami, and originated in the Bahamas and Dominican Republic.[1] Soon there was a huge glut of cocaine powder in these islands, which caused the price to drop by as much as 80 percent.[1] Faced with dropping prices for their illegal product, drug dealers made a decision to convert the powder to 'crack', a solid smokeable form of cocaine, that could be sold in smaller quantities, to more people. It was cheap, simple to produce, ready to use, and highly profitable for dealers to develop.[1] As early as 1981, reports of crack were appearing in Los Angeles, Oakland, San Diego, Miami, Houston, and in the Caribbean.[1]

So i reckon its a problem that Reason on my linux machine doesnt recognize those refill kits anymore, or theyre corrupted. Try to reinstall your refill kits. My situation is not that good, my refills are just copy and use packages, no installation. How to fix reason file bad format reason. But I can still open those 'bad format' songs with my laptop with those same refill kits installed.

Initially, crack had higher purity than street powder.[7] Around 1984, powder cocaine was available on the street at an average of 55 percent purity for $100 per gram (equivalent to $241 in 2018), and crack was sold at average purity levels of 80-plus percent for the same price.[1] In some major cities, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Houston and Detroit, one dose of crack could be obtained for as little as $2.50 (equivalent to $6.04 in 2018).[1]

According to the 1985–1986 National Narcotics Intelligence Consumers Committee Report, crack was available in Los Angeles, New Orleans, Memphis, Philadelphia, New York City, Houston, San Diego, San Antonio, Seattle, Baltimore, Portland, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Detroit, Chicago, Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Milwaukee, St. Louis, Atlanta, Oakland, Kansas City, Miami, Newark, Boston, San Francisco, Albany, Buffalo, and Dallas.

In 1985, cocaine-related hospital emergencies rose by 12 percent, from 23,500 to 26,300. In 1986, these incidents increased 110 percent, from 26,300 to 55,200. Between 1984 and 1987, cocaine incidents increased to 94,000. By 1987, crack was reported to be available in the District of Columbia and all but four states in the United States.[1]

Some scholars have cited the crack 'epidemic' as an example of a moral panic, noting that the explosion in use and trafficking of the drug actually occurred after the media coverage of the drug as an 'epidemic'.[8]

Impact by region[edit]

In a study done by Roland Fryer, Steven Levitt and Kevin Murphy, a crack index was calculated using information on cocaine-related arrests, deaths, and drug raids, along with low birth rates and media coverage in the United States. The crack index aimed to create a proxy for the percentage of cocaine related incidents that involved crack. Crack was a virtually unknown drug until 1985. This abrupt introductory date allows for the estimation and use of the index with the knowledge that values prior to 1985 are zero.[dubious][9] This index showed that the Northeast U.S. was most affected by the crack epidemic. The U.S. cities with the highest crack index were New York, Newark and Philadelphia.

The same index used by Fryer, Levitt and Murphy[10] was then implemented in a study that investigated the impacts of crack cocaine across the United States. In cities with populations over 350,000 the instances of crack cocaine were twice as high as those in cities with a population less than 350,000. These indicators show that the use of crack cocaine was most impactful in urban areas.

States and regions with concentrated urban populations were affected at a much higher rate, while states with primarily rural populations were least affected.[citation needed] Maryland, New York and New Mexico had the highest instances of crack cocaine, while Idaho, Minnesota and Vermont had the lowest instances of crack cocaine use.[citation needed]

Crime[edit]

Between 1984 and 1989, the homicide rate for black males aged 14 to 17 more than doubled, and the homicide rate for black males aged 18 to 24 increased nearly as much. During this period, the black community also experienced a 20–100% increase in fetal death rates, low birth-weight babies, weapons arrests, and the number of children in foster care.[11] The United States remains the largest overall consumer of narcotics in the world as of 2014.[12][13]

A 2018 study found that the crack epidemic had long-run consequences for crime, contributing to the doubling of the murder rate of young black males soon after the start of the epidemic, and that the murder rate was still 70 percent higher 17 years after crack's arrival.[14] The paper estimated that eight percent of the murders in 2000 are due to the long-run effects of the emergence of crack markets, and that the elevated murder rates for young black males can explain a significant part of the gap in life expectancy between black and white males.[14]

The reasons for these increases in crime were mostly because distribution for the drug to the end-user occurred mainly in low-income inner city neighborhoods. This gave many inner-city residents the opportunity to move up the 'economic ladder' in a drug market that allowed dealers to charge a low minimum price.

Crack cocaine use and distribution became popular in cities that were in a state of social and economic chaos such as Los Angeles and Atlanta. 'As a result of the low-skill levels and minimal initial resource outlay required to sell crack, systemic violence flourished as a growing army of young, enthusiastic inner-city crack sellers attempt to defend their economic investment.'[15] Once the drug became embedded in the particular communities, the economic environment that was best suited for its survival caused further social disintegration within that city.

Sentencing disparities[edit]

In 1986, the U.S. Congress passed laws that created a 100 to 1 sentencing disparity for the possession or trafficking of crack when compared to penalties for trafficking of powder cocaine,[2][3][4][5] which had been widely criticized as discriminatory against minorities, mostly African-Americans, who were more likely to use crack than powder cocaine.[6] This 100:1 ratio had been required under federal law since 1986.[16] Persons convicted in federal court of possession of 5 grams of crack cocaine received a minimum mandatory sentence of 5 years in federal prison. On the other hand, possession of 500 grams of powder cocaine carries the same sentence.[3][4] In 2010, the Fair Sentencing Act cut the sentencing disparity to 18:1.[6]

In the year 2000, the number of incarcerated African Americans had become 26 times the amount it had been in 1983.[citation needed]

In 2012, 88% of imprisonments from crack cocaine were African American. Further, the data shows the discrepancy between lengths of sentences of crack cocaine and heroin. The majority of crack imprisonments are placed in the 10–20 year range, while the imprisonments related to heroin use or possession range from 5–10 years which has led many to question and analyze the role race plays in this disparity.[17]

Post epidemic commentary[edit]

Writer and lawyer Michelle Alexander's book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness argues that punitive laws against drugs like crack cocaine adopted under the Reagan Administration's War on drugs resulted in harsh social consequences, including large numbers of young black men imprisoned for long sentences, the exacerbation of drug crime despite a decrease in illegal drug use in the United States, increased police brutality against the black community resulting in injury and death for many black men, women, and children.[18]

According to Alexander, society turned into a racist criminal justice system to avoid exhibiting obvious racism. Since African Americans were the majority users of crack cocaine, it provided a platform for the government to create laws that were specific to crack. This was an effective way to imprison black people without having to do the same to white Americans. Thus, there was a discourse of African Americans and a perpetuated narrative about crack addiction that was villainous and problematic. The criminalizing of African American crack users was portrayed as dangerous and harmful to society.

Alexander writes that felony drug convictions for crack cocaine fell disproportionately on young black men, who then lost access to voting, housing, and employment opportunities. These economic setbacks led to increased violent crime in poor black communities as families did what they had to do to survive.

Alexander explains the process of someone who is caught with crack: first, the arrest and the court hearing that will result in jail or prison-time. Second, the aftermath of permanent stigmas attached to someone who has done jail-time for crack, like being marked a felon on their record. This impacts job opportunity, housing opportunity, and creates obstacles for people who are left with little motivation to follow the law, making it more likely that they will be arrested again.

Dark Alliance series[edit]

San Jose Mercury News journalist Gary Webb sparked national controversy with his 1996 Dark Alliance series which alleged that the influx of Nicaraguan cocaine started and significantly fueled the 1980s crack epidemic.[19] Investigating the lives and connections of Los Angeles crack dealers Ricky Ross, Oscar Danilo Blandón, and Norwin Meneses, Webb alleged that profits from these crack sales were funneled to the CIA-supported Contras.

The United States Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General rejected Webb's claim that there was a 'systematic effort by the CIA to protect the drug trafficking activities of the Contras'. The DOJ/OIG reported: 'We found that Blandon and Meneses were plainly major drug traffickers who enriched themselves at the expense of countless drug users and the communities in which these drug users lived, just like other drug dealers of their magnitude. They also contributed some money to the Contra cause. But we did not find that their activities were the cause of the crack epidemic in Los Angeles, much less in the United States as a whole, or that they were a significant source of support for the Contras.'[20]

Influence on popular culture[edit]

In documentary films[edit]

- High on Crack Street: Lost Lives in Lowell (1995)

- Cocaine Cowboys (2006)

- Crackheads Gone Wild (2006)

- American Drug War: The Last White Hope (2007)

- Freakonomics (2010)

- Planet Rock: The Story of Hip-Hop and the Crack Generation (2011)[21]

- The Seven Five (2014)

- Freeway: Crack in the System (2015)

- 13th (2016)

In documentary serials[edit]

- Drugs, Inc. (2010–present)

Snowfall (produced by FX)

In film[edit]

- Death Wish 4: The Crackdown (1987)

- Colors (1988)

- King of New York (1990)

- New Jack City (1991)

- Boyz n the Hood (1991)

- Deep Cover (1992)

- Menace II Society (1993)

- Above the Rim (1994)

- Fresh (1994)

- Dead Presidents (1995)

- Belly (1998)

- Streetwise (1998)

- Training Day (2001)

- Paid in Full (2002)

- Shottas (2002)

- The Wire (2002)

- Dark Blue (2002)

- Get Rich or Die Tryin' (2005)

- Notorious (2009)

- Life Is Hot in Cracktown (2009)

- Moonlight (2016)

- Snowfall (2017)

In video games[edit]

- Narc (1988)

- Grand Theft Auto: Vice City (2002)

- Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (2004)

- Grand Theft Auto: Vice City Stories (2006)

- Scarface: Money. Power. Respect. (2006)

- Scarface: The World Is Yours (2006)

- Hotline Miami (2012)

Research books[edit]

- Sudhir Venkatesh (Indian American sociologist scholar and reporter)

- Freakonomics (2005) – Chapter: 'Why Do Drug Dealers Still Live With Their Moms'

- American Project. The Rise and Fall of a Modern Ghetto, Harvard University Press, 2000

- Off the Books. The Underground Economy of the Urban Poor, Harvard University Press, 2006

- Gang Leader for a Day: A Rogue Sociologist Takes to the Streets, Penguin Press, 2008

- Floating City: A Rogue Sociologist Lost and Found in New York's Underground Economy, Penguin Press, 2013

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abcdefgh'DEA History Book, 1876–1990' (drug usage & enforcement), US Department of Justice, 1991, USDoJ.gov webpage: DoJ-DEA-History-1985-1990.

- ^ abJim Abrams (July 29, 2010). 'Congress passes bill to reduce disparity in crack, powder cocaine sentencing'. Washington Post.

- ^ abcBurton-Rose (ed.), 1998: pp. 246–247

- ^ abcElsner, Alan (2004). Gates of Injustice: The Crisis in America's Prisons. Saddle River, New Jersey: Financial Times Prentice Hall. p. 20. ISBN0-13-142791-1.

- ^ abUnited States Sentencing Commission (2002). 'Cocaine and Federal Sentencing Policy'(PDF). p. 6. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 15, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

As a result of the 1986 Act .. penalties for a first-time cocaine trafficking offense: 5 grams or more of crack cocaine = five-year mandatory minimum penalty

- ^ abc'The Fair Sentencing Act corrects a long-time wrong in cocaine cases', The Washington Post, August 3, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^The word 'street' is used as an adjective meaning 'not involving an official business location or permanent residence' such as: 'sold on the street' or 'street people' in reference to people who live part-time along streets.

- ^Reinarman, C. and Levine, H. (1989). 'The Crack Attack: Politics and Media in America's Latest Drug Scare'. In J. Best (ed.). Images of Issues: Typifying Contemporary Social Problems. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) see also Reeves, J. L. and Campbell, R. (1994). Cracked Coverage: Television News, the Anti-Cocaine Crusade, and the Reagan Legacy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^Beverly Xaviera Watkins, et al. 'Arms against Illness: Crack Cocaine and Drug Policy in the United States.' Health and Human Rights, vol. 2, no. 4, 1998, pp. 42–58.

- ^Fryer, Roland G., et al. 'Measuring Crack Cocaine And Its Impact.' Economic Inquiry, vol. 51, no. 3, July 2013, pp. 1651–1681., doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.2012.00506.x.

- ^Fryer, Roland (April 2006). 'Measuring Crack Cocaine and Its Impact'(PDF). Harvard University Society of Fellows: 3, 66. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^How bad was Crack Cocaine? The Economics of an Illicit Drug Market. Researched by Steven D. Levitt and Kevin M. Murphy [1].

- ^The World FactbookArchived 2010-12-29 at the Wayback Machine. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 2014-05-12.

- ^ abEvans, William N; Garthwaite, Craig; Moore, Timothy J (2018). 'Guns and Violence: The Enduring Impact of Crack Cocaine Markets on Young Black Males'.Cite journal requires

journal=(help) - ^Inciardi, 1994

- ^Durbin's Fair Sentencing Act Passed By House, Sent To President For Signature, durbin.senate.gov. Retrieved September 30, 2010. Archived March 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^'Conclusions'(PDF). www.bjs.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^Alexander, Michelle (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press. ISBN1595586431.

- ^Peter Kornbluh (Jan–Feb 1997). 'Crack, the Contras, and the CIA: The Storm Over 'Dark Alliance''. Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^https://oig.justice.gov/special/9712/ch12.htm#Chapter%20XII:

- ^Viera, Bené (November 26, 2011). ''Planet Rock' Shows The Power Of Hip-hop'.

Further reading[edit]

- Reinarman, Craig; Levine, Harry G. (1997). Crack In America: Demon Drugs and Social Justice. University of California Press. ISBN978-0520202429.

External links[edit]

- DEA History in Depth (1985–1990), The Crack Epidemic at the DEA

- Oversight hearing of the DEA by the Subcommittee on Crime; July 29, 1999 at The House

- 'How Bad Was Crack Cocaine?' at the Booth School of Business

- 'Cracked up'; analysis of the epidemic at Salon

Abstract

Background

In Brazil, crack cocaine use remains a healthcare challenge due to the rapid onset of its pleasurable effects, its ability to induce craving and addiction, and the fact that it is easily accessible. Delayed action on the part of the Brazilian Government in addressing the drug problem has led users to develop their own strategies for surviving the effects of crack cocaine use, particularly the drug craving and psychosis. In this context, users have sought the benefits of combining crack cocaine with marijuana. Our aim was to identify the reasons why users combine crack cocaine with marijuana and the health implications of doing so.

Methods

The present study is a qualitative study, using in-depth interviews and criteria-based sampling, following 27 crack cocaine users who combined its use with marijuana. Participants were recruited using the snowball sampling technique, and the point of theoretical saturation was used to define the sample size. Data were analyzed using the content analysis technique.

Results

The interviewees reported that the combination of crack cocaine use with marijuana provided “protection” (reduced undesirable effects, improved sleep and appetite, reduced craving for crack cocaine, and allowed the patients to recover some quality of life).

Conclusions

Combined use of cannabis as a strategy to reduce the effects of crack exhibited several significant advantages, particularly an improved quality of life, which “protected” users from the violence typical of the crack culture.

Crack use is considered a serious public health problem in Brazil, and there are few solution strategies. Within that limited context, the combination of cannabis and crack deserves more thorough clinical investigation to assess its potential use as a strategy to reduce the damage associated with crack use.

Background

The use of crack cocaine emerged in Brazil in the early 1990s in the city of São Paulo [], and the first drug seizure made by the Civil Police of São Paulo in 1991 although crack cocaine was reportedly present in the country as early as 1989 [2]. The status of healthcare in Brazil at that time was extremely worrisome. An AIDS epidemic was ravaging the country, particularly in the state of Sao Paulo, where people who use injection drugs (IDUs) constituted one of the groups susceptible to viral infection due to the route of drug administration []. The majority of government and healthcare professional attention was focused on this situation [, ]. Because of this serious public health problem and the emergence of crack cocaine, several IDUs started to use this new drug in an attempt to protect themselves from the threat of contracting the virus via an intravenous route of administration []. This change in the administration route was not a very difficult step given that crack cocaine offered some “advantages”; it was inexpensive, its “powerful” effects were achieved in a matter of seconds, it was easily administered, and it was considered to be a “clean” drug because it did not have the potential to transmit HIV or other STDs due to the administration route [, ]. Initially, the use of crack cocaine functioned as an informal harm reduction strategy. According to Mesquita et al. [], the transition in administration route may have contributed to reducing HIV infection rates during the period from 1991 to 1999, which decreased from 63 to 42 % in the city of Santos, the city with the highest rate of HIV infection. At that time, crack cocaine use was not a problem that attracted the attention of the authorities, although there were already reports of its devastating effects []. The establishment of the Brazilian “cracolandias” (“crack lands”) - public places where crack cocaine users met to consume the drug out in the open - was also not sufficient to elicit more rapid action from the state regarding crack cocaine use []. Perhaps as a result of the scenario at that time (the AIDS epidemic), the State’s actions in confronting the drug problem were delayed, leading crack cocaine users to devise their own solutions to the problems arising from their use of this drug. The potential for harm caused by crack cocaine is quite high when the negative outcomes produced are considered, making its abuse a public health problem in Brazil today []. The harmful effects of crack cocaine include the high degree of disintegration of socioeconomic and mental health; the intense involvement with crime, marginalization, violence, prostitution, and multiple sexual partners; and the consequent increased potential for HIV infection [–].

Ribeiro et al. [] examined the strategies developed by users and found that they employed simple strategies, such as using the drug in protected locations; avoiding visibility; fulfilling commitments with drug traffickers to avoid reprisals, including death; staying quiet in the vicinity of the “bocada” (drug trafficking area) and not arousing the attention of the neighborhood and the police; and combining other drugs, such as marijuana or alcohol, with crack cocaine use. Chaves et al. [] investigated the strategies employed by crack cocaine users to control their craving and observed strategies similar to those used in the study mentioned above; however, they also noted the combination of crack cocaine use with other drugs, especially marijuana and alcohol.

The use of marijuana seems to be common among crack cocaine users; however, few studies have considered the user’s opinions in addressing this phenomenon.

The current study used a sample that was selected based on the criteria for purposeful sample, exhibiting appropriate level of rigor for satisfactory qualitative study. However, the most common combination mentioned by other authors involved adding crack rocks to marijuana inside of a cigar [17]. However, in the present study, additional cannabis combinations were investigated.

In this context, the approach used in the present study was justified (i.e., the users themselves reported the “advantages” and disadvantages of this combination based on their knowledge, values, and points of view, allowing for an understanding of their reality).

Methods

A qualitative methodology was used because it allowed us to analyze study participants’ beliefs about the combination of marijuana and crack cocaine based on their own views and concepts [18–20].

Sample recruitment

Seven key informants (KIs) were selected during the first phase of the study - five psychiatrists and two psychologists – who had varied knowledge about the study topic and the study population [20]. These KIs were invited for an informal conversational interview without a previously prepared script. Relevant questions regarding the topic arose in the context of these conversations [–23]. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed, and the data generated was then used by the researchers to prepare an interview script that was used with the study participants (crack cocaine users) [20]. Due to difficulties in accessing the study population due to the illegality of crack cocaine use, some of the KIs also played a gatekeeper role (i.e., they provided access to the study participants) [18]. Because the gatekeepers were known by the study population, they inspired the trust of the drug users, facilitated the participation of that population in the study, and were the first point of contact between the study population and the researchers. Each KI identified potential participants and discussed the study with them prior to introducing the researchers. Those who agreed to participate were instructed to contact the researchers. In-depth interviews were conducted using purposeful sampling, the components of which followed particular criteria (criterion sampling) [20]: Crack cocaine users who were older than 18 years of age and who had combined crack cocaine with marijuana use a minimum of 25 times, thereby ensuring that experimental users were not included in the sample []. These criteria led to a sample size of 27 participants, all of whom were selected in the city of São Paulo during the years 2012–2013. The first interviewees who were contacted by the KIs identified other possible participants, thereby using the snowball technique to compose the sample. Sampling using the snowball technique starting with the first interviewee created a chain of interviewees [23, 25]. To include the largest possible number of user profiles in the sample who met the inclusion criteria proposed, various chains of interviewees were sought, and seven chains were identified, which ranged from 3 to 5 individuals each. The sample size was adequate to cover all of the topics of interest and various user profiles. This assumption was met when the interviewees’ responses became redundant. At this point, termed the theoretical saturation point, the lack of new information and the repetition of responses were identified [18, 20, 23].

Instruments used

Semi-structured interviews were conducted using a script of topics that were selected based on the information provided by the KIs [20, 22]. The script was composed of previously standardized questions to facilitate comparisons among responses and reduce interviewer interference. Additional questions emerged to clarify specific topics during each interview, allowing for improvement of subsequent understanding [22, 23]. The script consisted of socio-demographic data, history of drug use, history of crack cocaine use, associated marijuana use, and damages/“advantages” of the combination. The questions relating to the socioeconomic data were evaluated using the Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria 2008 scale, published by the ABEP (Brazilian Association of Research Companies-Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa) [26]. This scale mainly considers the consumer goods possessed by the family and classifies respondents into classes A1, A2, B1, B2, C, D and E (A1 is the category with the greatest ownership, whereas E delineates a lack of ownership and includes the homeless). The criteria for dependency, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) [27], were also incorporated into the script. After obtaining the consent of the interviewees, the interviews were recorded, each of which lasted approximately 70 min.

Qualitative analysis of the content

Each interview was identified by an alphanumeric code in which the first letter was the first initial of the interviewee’s name, followed by his or her age and gender. The interviews were transcribed and reviewed by the researchers. They were then analyzed using the content analysis technique based on Bardin’s theoretical framework [28]. The various parts of the interviews were split and then grouped according to each research theme. For the analysis, NVivo Software Version 10 was used, which allowed for greater data analysis consistency and facilitated organization. The importance of the themes identified was analyzed by considering the emic approach. This step, defined as categorization, was developed by the two researchers who independently and simultaneously analyzed the data. Then, these two analyses were compared to obtain consistency and coherence in the results. Finally, inferences supporting the explanations were initiated and conclusions were generated.

Quotes from the interviewees’ statements are presented in the results section; they are identified by their code and shown in italics.

Ethical consideration

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (CEP 1602/11). In the study, oral informed consent was obtained from each participant at the beginning of the initial interview after they were given information about the study and informed that they could withdraw at any time. With permission, interviews were recorded using a digital recorder and later transcribed in full. Anonymity of participants was maintained.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

The sample, which contained 27 crack cocaine users between the ages of 19 and 49 years (mean 25.9), consisted mostly of 21- to 30-year-old males who had received little education (only elementary school), belonged to a low social class (class E) [26], were unemployed, were living in shelters or on the street without family and were crack cocaine-dependent. All of the participants proved to be crack cocaine-dependent according to DSM-IV [27] criteria, and nearly 70 % of them were also reported to be marijuana-dependent.

Drug use was not always recreational. All of the participants in the sample reported having had problems with some of the drugs cited, but crack cocaine was the drug that most affected all aspects of their lives. Social problems, such as robberies and loss of family, job, and social status, were most commonly cited, followed by physical injuries resulting from assaults, impaired appearance, etc. Cravings and transient paranoid symptoms were described as the effects of the drug that most contributed to these damages.

The participants reported having used various self-devised strategies to either stop crack cocaine use or overcome the problems caused by it, including seeking help in religion, avoiding contact with crack cocaine users, and the use of other drugs combined with crack cocaine.

Combination with other drugs

According to the interviewees’ statements, the combination of crack cocaine and marijuana was not the only drug combination used. Even sporadically, drugs, such as alcohol, hallucinogens (Ecstasy), and snorted cocaine, and medications, such as benzodiazepines, were also used in combination with crack cocaine in an attempt to either increase the pleasurable effects or minimize the unpleasant effects. However, as with the combination of crack cocaine and marijuana, the combination with alcohol was also mentioned often.

The criteria used to choose a drug to be combined with crack cocaine were based on the experience of other users, experimentation, and the individual evaluation of the effects of the combination tested.

Reasons cited for combining crack cocaine with marijuana1

Based on the interviewees’ statements, it became evident that in the context of crack cocaine use, the participants attributed a “protection” role to marijuana that was revealed in several ways.

Reduction of unpleasant effects: The participants attributed relaxing properties to marijuana, which interfered with the effects of crack cocaine by decreasing those effects that were considered to be undesirable. Additionally, participants considered that the effects resulting from the combination were pleasant. Transient paranoid symptoms, which are a typical effect of crack cocaine use and according to users can cause fear, distrust, and sometimes violent behavior, were the effects that were most commonly mentioned by the interviewees as being suppressed in the presence of marijuana.

When I mix marijuana with crack, the effect of marijuana is stronger than the effect of crack cocaine, which then curbs paranoia (psychosis) and controls cravings (G38MC).

The “mesclado” (“mix”) makes me fly. It takes away the wickedness of the rock. I do not look for pieces of rock on the ground, like a fool. The effect of the “mesclado” is better; it is very different (V43MC).

Reduction of crack cocaine-seeking behavior: The serenity caused by marijuana helped the participants control their cravings so that the desire to smoke was reduced. Because of this effect, strategies to obtain the drug, such as thefts and robberies, did not need to be used, which protected the users from possible fatalities resulting from these activities. The participants stated that marijuana caused a type of “numbness” of the mind, which made them “forget” about crack cocaine, even if only temporarily. The focus on crack cocaine was displaced by the effects resulting from the combination.

I am alert to everything, but then the effect of marijuana makes me feel calm and I do not think about stealing. I do not think about doing something wrong. I just stay there enjoying that effect, understand? (G38M)

Reduction of aggressiveness: This issue was highlighted as having a marked effect on the crack cocaine use culture. When asked about the influence of marijuana on this effect, the vast majority of participants stated that there was a reduction in, or even absence of, aggressiveness.

The pure rock makes me aggressive because I want to smoke more, and if someone stops me from doing this, I become violent, even if it is a family member. With marijuana, I control this situation because I am more relaxed, less anxious. (G24M)

Quality of life

Participants also reported that the combination of the two drugs allowed for the partial recovery of the quality of life that was lost with crack cocaine use. Basic human needs that were previously compromised by the use of crack cocaine were regained with the use of marijuana combined with crack cocaine. Sleep, hunger, and sex are examples of this well-being that were cited by the interviewees.

…with marijuana, I sleep well. I eat well. I have good sex. It makes me calm; the same feeling as taking diazepam, a tranquilizer. I become more cool (nice)… (V49M)

Savings

According to some interviewees, mixing crack cocaine with marijuana helped them to save money to buy crack cocaine because a portion of their crack cocaine use was replaced by marijuana use. According to the participants’ reports, this resulted in a higher crack cocaine yield.

It lasts longer. Assuming that I smoke a crack cocaine rock that costs 10 Brazilian reais (approximately $5) in a half hour, with marijuana, it will take one hour. I split it into small bits, I stop, and then I smoke more.” (R27M)

The combination of crack cocaine with marijuana was not always perceived as beneficial by the user. Those who disliked the combination of crack cocaine with marijuana attributed this dislike to the reasons outlined below.

Decrease in the potency of the drug: A small number of participants did not consider the combination of crack cocaine with marijuana to be beneficial; specifically, the action of marijuana on the effects of crack cocaine (i.e., reducing its intensity) was not well accepted by everyone. The calm and relaxation promoted by the combination that represented a gain for some of the participants was the cause of displeasure for others, so that the participants started using the “mesclado”, but after a period of time, they went back to smoking crack cocaine alone, without combining it with marijuana.

I lost interest because the “mesclado” makes the person much more quiet… And I do not want to be quiet, not in that way… so I tried the pure crack cocaine and found that the pure crack cocaine made me more alert… (P34M)

Undesirable effects: Participants reported the occurrence of undesirable psychological effects when marijuana was used, reinforcing the idea that drug use is an individual experience.

If I smoke some marijuana, I do not feel good. I feel depressed. I feel very bad. I think it is because I used too much crack, so it affected my brain a bit. If I smoke a joint today, I feel worse than if I had smoked a rock. I feel very depressed. (M23F)

The sequence of the marijuana and crack cocaine combination

The sequence of the marijuana and crack cocaine combination seemed to be of great importance in the effects resulting from combining the two drugs. Some of the participants preferred to use marijuana before smoking crack cocaine, whereas others preferred to use it after smoking crack cocaine, but the simultaneous use of marijuana and crack cocaine was most commonly observed in this sample (“mesclado” or “pitilho”).

Simultaneous use of marijuana and crack cocaine (mesclado)

As mentioned previously, the “mesclado” was the preferred manner of combining these two drugs. The participants attributed this preference to several factors, which are outlined below.

Does not attract attention on the street: According to the interviewees, smoking from a pipe makes crack cocaine use obvious; they are identified as users anywhere they use a crack pipe. Using a cigarette, in which marijuana is mixed with the rock (crack cocaine), is more “protective”. These users face no discrimination because they are not identified as crack cocaine users (known as a “craqueiro” in Brazil). Additionally, some of the interviewees stated that the unpleasant effects, mainly the transient paranoid symptoms, disappeared, and the combined use of marijuana and crack cocaine also helped them to remain calmer, which contributed to greater social acceptance and consequently decreased the high degree of marginalization to which they were subjected.

I can smoke in a park without any problem. Using only the rock, I get paranoid (psychotic), suspicious of everyone. I just want to be hidden from view. I think about stealing all the time. (R31M)

The interval between consumption is increased: The interviewees stated that when they smoked the “mesclado”, it took longer for them to want to smoke it again, resulting in them consuming a smaller amount of crack cocaine. With the “mesclado”, 1 to 2 h elapsed before they repeated the drug use; in contrast, when they used only crack cocaine, this period of time was reduced to 5 or 10 min.

Use of marijuana before crack cocaine

A few interviewees reported using marijuana before crack cocaine because they claimed that in such circumstances, they became more relaxed and calmer and would not consume crack cocaine afterwards while they experienced this tranquility. Some of the interviewees revealed that the only way to change this condition was to consume alcohol to “break” this state and then return to smoking crack cocaine after marijuana use. These implications led them to stop using marijuana in this manner, replacing it with other manners of use, the most common of which was the “mesclado”.

Use of marijuana after crack cocaine

Marijuana was used in this sequence with the same goal as that of the previous sequence, which was the reduction of the undesirable effects of crack cocaine. Those who consumed marijuana after crack cocaine reported that it prevented them from seeking more crack cocaine to continue using it.

I smoked it [marijuana] afterwards to stop, understand? Because after the effect of marijuana… that was it! Then, I was relaxed.” (C33M)

Some users reported a slightly different goal: after they had consumed all of the crack cocaine and did not have the possibility of getting more of the drug, they smoked marijuana to abolish the desire to smoke more crack.

It is important to highlight that in this sample, combinations with other drugs were aimed at reducing the undesirable effects of crack cocaine and allowing the users to smoke it in a calmer manner. Accordingly, with the exception of one user, none of the participants attempted to replace crack cocaine with another drug (in this case, marijuana). Despite the positive results promoted by the use of marijuana before crack, some of the interviewees altered the sequence of this combination due to the unfavorable environment created by this drug, which made the use of crack cocaine more difficult.

Discussion

The present study examined the combination of crack cocaine and cannabis as an informal alternative to cope with the use of crack cocaine. This combination has been previously mentioned in other studies by Brazilian authors [–17, ].

The study sample consisted mainly of young men of low socioeconomic status, with little schooling, who were living on the street. These characteristics are consistent with the profile of Brazilian crack users recently described by the government [30]. Thus, the study findings are likely reflective of the broader population of crack users in Brazil given the similarities in characteristics noted here.

In their narratives, the interviewees described the benefits of the cannabis-crack combination. A reduced craving, which is considered the main cause of dependence and involvement in high-risk situations to obtain the drug [], was one of the advantages most often mentioned by the participants. In a study conducted with a convenience sample of six users undergoing treatment, Andrade et al. [17] found that a reduced craving was the greatest benefit of using the crack-cannabis combination. Participants in the present study additionally reported a reduction of transient paranoid symptoms, which sometimes lead to violence [, ], as a positive outcome of the combination.

The interviewees emphasized that the improved quality of life as a result of eliminating or reducing cravings and paranoid symptoms was the most positive effect of using the cannabis-crack combination. This effect protected them from marginalization and/or violent environments, which are the main causes of death, favoring the reduction of their marked vulnerability in the crack cocaine use culture []. Additionally, a persistent relationship with society is highly valuable in terms of potential access to healthcare services, which might help improve their wellbeing []. This combination also resulted in decreasing crack cocaine-seeking behavior, which in turn reduced use of crack cocaine, increased monetary savings, and increased survival. The unhealthy appearance of crack cocaine users due to drug-induced appetite inhibition was compensated for by marijuana use, which awakened the appetite, causing weight gain, and also improved sleep [].

The most common combination mentioned by other authors and the present study participants involved adding crack rocks to marijuana inside of a cigar [17]. However, in this study, they also reported other methods of drug intake, such as using cannabis before or after crack. In either case, the interviewees slowed or even stopped their crack use due to the state of relaxation induced by cannabis. It is worth noting that participants were not always pleased with the outcome because their focus was not on quitting crack. Nevertheless, these types of combinations should be given more attention in strategies based on the replacement of drugs associated with multiple physical and mental complications by less damaging drugs.

The therapeutic effects of cannabis have been known for a long time []. Carlini et al. [] and Leite and Carlini et al. [], in the 1980s, demonstrated the medicinal properties of marijuana, especially the anticonvulsant properties of the drug.

Webb et al. [] observed 100 patients who were using cannabis for medicinal purposes, and the authors obtained significant results, including the fact that 50 % of the patients experienced reduced levels of stress and anxiety, 45 % experienced improved sleep, and 12 % experienced improved appetite. Brunt et al. [] also confirmed these beneficial effects of cannabis.

These studies provide support for the action of marijuana on the effects of crack cocaine. For example, the transient paranoid symptoms characteristic of crack cocaine use are suppressed by a component of cannabis called cannabidiol that has effective antipsychotic properties [–]; furthermore, the hypnotic effects of components of cannabis account for the stabilization of sleep in the user, which is extremely impaired with the use of crack cocaine [].

However, the benefits of the use of marijuana combined with crack cocaine do not occur without consequences. Whereas most of the participants emphasized the benefits afforded by the cannabis-crack combination, it was clear that the intensity of the pleasurable stimulating effects of crack were decreased with cannabis use. This effect prevented wider acceptance of the strategy and led some users to abandon the method. Another notable fact is that 70 % of the sample met the DSM-IV criteria [27] for cannabis dependence, which must be taken into consideration in assessing the risk/benefit ratio of the cannabis-crack combination.

The value of this combination is difficult to evaluate and discuss in detail due to the illegality of cannabis in Brazil [44]. This fact has prevented important advancements from being made in the investigation of whether cannabis could be used as an alternative to reduce the damage caused by the abuse of and dependency on crack cocaine [45].

Conclusion

Combined use of cannabis as a strategy to reduce the effects of crack exhibited several significant advantages, particularly an improved quality of life, which “protected” users from the violence typical of the crack culture.

Crack use is considered a serious public health problem in Brazil, and there are few solution strategies. Within that limited context, the combination of cannabis and crack deserves more thorough clinical investigation to assess its potential use as a strategy to reduce the damage associated with crack use.

Study limitations

This study was a preliminary study with a qualitative approach. The study sampled 27 participants and was not representative of the total population of crack users in Brazil.

Study strengths

Given the serious and growing problem posed by crack use in Brazil and the few possible solutions available, the benefits of combined cannabis and crack demonstrated in the present study should not be dismissed. The results of the present study could aid in emerging discussions in Brazil on the therapeutic properties of marijuana.

Acknowledgements

We thank CAPES for the master fellowship to the first author.

Footnotes

1This combination, referring to when the two drugs are used together, was given various names in different regions of the country. In the southeast, it was known as “mesclado” (mix), and in the northeast, it was known as “pitilho”).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JRG managed data collection, conducted preliminary data analysis and drafted the manuscritpt. SAN conducted the final data analysis, revised the manuscript, designed the research questions and was responsible for general coordination. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Janaina R. Gonçalves, Email: moc.liamtoh@oib.ur.anaj.

Solange A. Nappo, Email: moc.liamg@oppanegnalos.